Paul Vidich’s The Good Assassin raises a number of questions, some of which have to do with the action in this “Cold War spy fiction” that just happens to be set in Havana, on the eve of the triumph of Fidel Castro’s Revolution; and others that have more to do with why we read in the first place. In other words, what is any particular reader looking for when they open a book?

As far as this particular novel goes it is entertaining, to a degree, pacey enough, although it does not have much depth. There is little or none of the subtext that I personally prefer to deal with in the books I read. The characters are pretty flat, rendered with little nuance, and therefore not complex. And the portrait of Havana in 1958 is limited, and almost stereotypical, the sense of the place tinted by the lens of the genre. More than once I thought that The Good Assassin could be located just about anywhere, at any time, it really didn’t matter when and where.

On the level of language Vidich strains more often than he accomplishes, and it shows. Some lines strike cold and hard and fast and true, and others are practically unintelligible:

Mueller didn’t agree to the assignment at their lunch, but his silence was confederate to the director’s request. He knew one week was an impossibly optimistic estimate of the time he’d be in Cuba, but the idea that he would escape campus lethargy had tart appeal. His sabbatical was upon him, but he’d lost interest in his research on the puns and paradoxes in Hamlet, a lively but binocularly narrow topic, and he was out of sorts with his life.

Despite pretty much everything in this novel being clichéd to some degree, this paragraph early in the story—which goes on in this vein—provides the reader with a pretty good idea of who and what Mueller is, even if Mueller’s character, as developed throughout the book, remains basically two dimensional, and therefore unrealized.

Of course Mueller is going to bed Katie, the plucky free-lance photographer he’s hired as part of his cover. But what, really, does this mean?

They found themselves tempted by the idea that they were more interesting and spontaneous than the physics of a professional calculation.

Or:

Self-deprecation was a strategy too. He knew better than to allow spite to jeopardize a deceit.

There are plenty of these presumably witty but not-entirely-clear affirmations, lines that must sound good to Vidich’s ear and that do sound like the sort of thing that might come out of Humphrey Bogart’s mouth—in voice over, if necessary—but are, unfortunately, closer to gibberish. Later Vidich will write, “Sunlight flushed shy thoughts from his mind” followed by this:

Mueller felt in that part of his mind that calibrates threats before they are obvious the risk of being made complicit in a crime.

This, at least, is straight forward and comprehensible and it has the necessary crime-thriller beat. But too often Vidich forgets Ezra Pound’s dictum that “Fundamental accuracy of statement is the sole morality of writing.”

This lack of fundamental accuracy applies not only to his language, but to the observations of his characters and the action. At the very beginning of the novel Mueller flies from Connecticut to Cuba, presumably passing through Miami. And yet he looks out the window as they begin their descent towards Havana and sees the Sierra Maestra, where Fidel Castro launched his efforts to overthrow Batista. Unfortunately for the reader who knows anything about Cuban geography this is impossible: the flight from Miami usually enters from the west and the Sierra Maestra is located east of Havana: over 400 miles away, as the crow flies.

In terms of a sense of place, twice in the space of four short pages Vidich describes the landscape—from Havana to Camaguey—as “unchanging:”

The four of them were driving through a monotonous section of the Carretera Central several hours into their journey to Camaguey. Fields of sugar cane and thorn brush filled the view, and ahead, still a ways off, the russet hills of their destination…They smiled at Mueller’s comment, but their eyes drifted back to the unchanging landscape.

After winding through more “thorn brush,” whatever that might be, specifically—what this brush might actually look like, or how looking at so much of it might make someone feel—Mueller looks at Liz and sees a “sad expression” on her face “that was a window onto a terrible grief,” as “she gazed out at the barren, unchanging landscape of dry red earth on the passing hills.”

Just as the landscape, and setting in general, is treated in this offhand manner, so too are the characters handled, not as if they were individuals leading unique lives, but as if they were stereotypes of the brusque heartless American rancher-businessman and the pitiful adulterous-of-necessity wife. Katie—the spunky photojournalist—actually has a bit of character, but her role in the story is minor. Nothing about this story carries the conviction of any kind of truth, either of place or character.

But the story is full of these baffling lines, that might make the reader pause and puzzle over Vidich’s intent:

He began to see there was a way to think about Graham’s life as spun from a single filament of fact woven loosely into a fabric of sheer audacity.

The jeopardy of the moment deepened and turned profound. Smells of rain drifted to them and branches ripped from trunks flew into the air. A woman with wounded memories finds it helpful to succor the pain by sharing thoughts with a friend. And so it happened.

Perfect weather at the start of All Saint’s Week provided the opportunity to honor the promise of the day.

One of the major problems of this novel is that nothing is believable. Not that a reader can’t or won’t follow the action and wonder what will happen next, without disbelieving what they’re being told. But rather the reader is being told too much, and too little is demonstrated in this novel. We are supposed to believe this conversation is taking place during a hurricane, but nothing Vidich does with his prose suggests the experience of a hurricane. The threat of violence is supposed to be all around these characters, but the reader never feels this threat of violence.

Vidich writes, at the beginning of Chapter 9, near the end of the novel, and shortly before its climax, “The little party was using the charm of a fisherman’s shack to escape the oppression of the war. They all wanted to embrace the trip as a way to lighten the day, contain their drama and preserve decorum, but Mueller felt jeopardy in the fragile peace.”

Vidich uses the word ‘jeopardy’ here as above to try to convince the reader, via the use of a single word, and by relying almost exclusively upon that word’s definition[1] that his characters are involved in a dangerous situation. But the reader—or I, at least—never feels this. There is no sense of threat percolating beneath the surface of this novel, no subtext of real danger. Everything is almost distressingly obvious and obviously fabricated.

So it shouldn’t have been any surprise to me to see how Vidich used—or usurped—certain motifs and characters from The Great Gatsby to generate his own characters (Jack is almost interchangeable with Tom, although the portrayal of the latter is much more sophisticated) and the climax of his novel, in which Mueller—after a scene almost identical to the scene in Fitzgerald’s novel in which Gatsby tells Tom that Daisy loves him and she finally encourages everyone to go into town in order to relieve the tension created by her dilemma—hits and kills Jack’s lover with the car while he drives a distraught Liz home.

There is also the issue of the stilted speech. At the fisherman’s shack, where Jack chose to confront and expel Graham, presumably from their home as well as their lives, Liz says to him, her husband, “You let the garden of our marriage go to seed. There were flowers we planted to remind us who we used to be, but they’ve withered. Dried up here in this place. All our sunshine days of memory are not enough to let us ignore the weeds.”

The Good Assassin is a quick easy read, that could have been set anywhere, at any period of history. Just as the setting is immaterial, so are the characters, because they never come to life, and instead remain two-dimensional cardboard stereotypes of characters incapable of devising their own story.

To match and balance the impossible sighting of the Sierra Maestra at the beginning of the novel there is the shootout in the belfry of the church where Graham had arranged to meet Liz so that they could leave on a DC 3 at the end of the novel. Mueller notices two green Oldsmobiles parked outside, to indicate that Pryce—the FBI guy—has not only come with Alonzo, head of SIM, the Cuban Military Police, but is in cahoots with him. But how can a reader believe this? These guys are there to take down Graham, who is suspected of delivering arms to the rebels, and they take two cars, each driving one of them, and bring no reinforcements? Talk about jeopardy!

I’ve said enough. This novel requires some real suspension of disbelief, but that’s precisely what many people read for: in order to ‘escape reality.’

[1] Danger of loss, harm, or failure, a term originally used in chess and other games to denote a problem, or a position in which the chances of winning or losing were evenly balanced, hence ‘a dangerous situation.’

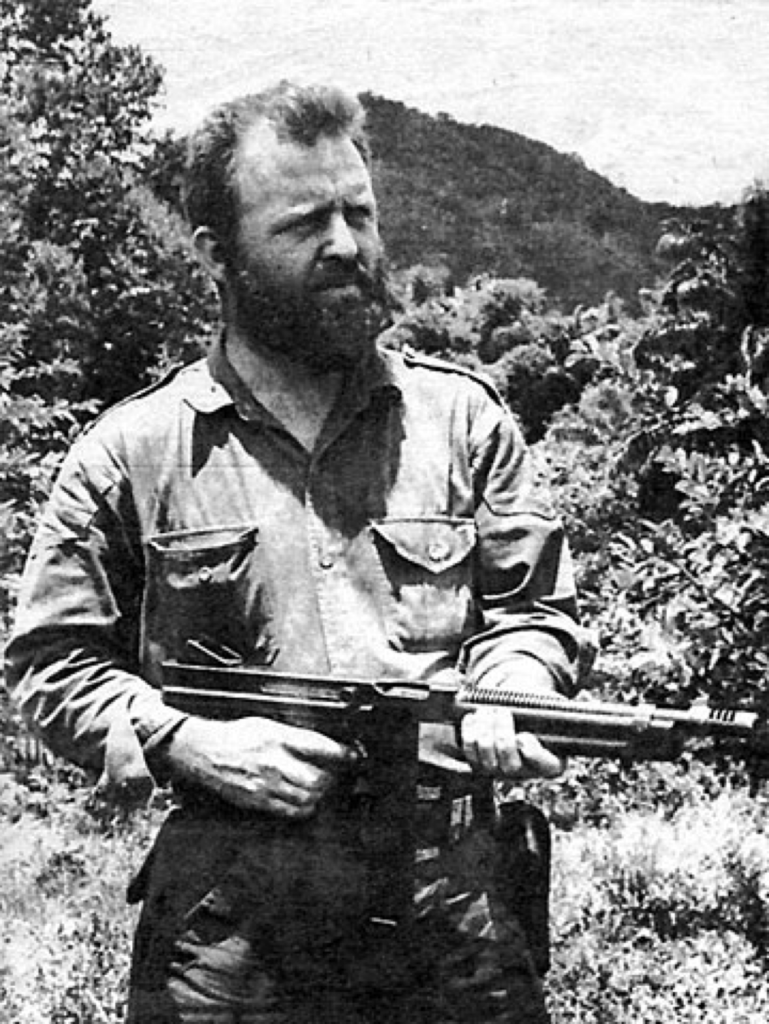

By Cuban revolutionary movement http://www.latinamericanstudies.org/william-morgan.htm, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=73744225